By Thomas Zauner

Current climate goals require the removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. However, how exactly this should happen is up for debate. Researchers at the University of Vienna and the Potsdam Research Institute for Sustainability took a close look at the emission reduction plans of several major EU industry sectors and found a substantial but underspecified reliance on uncertain carbon removal technologies. This enables them to project currently highly emission-intensive business models into the future, in some cases ignoring the need to phase out fossil fuels.

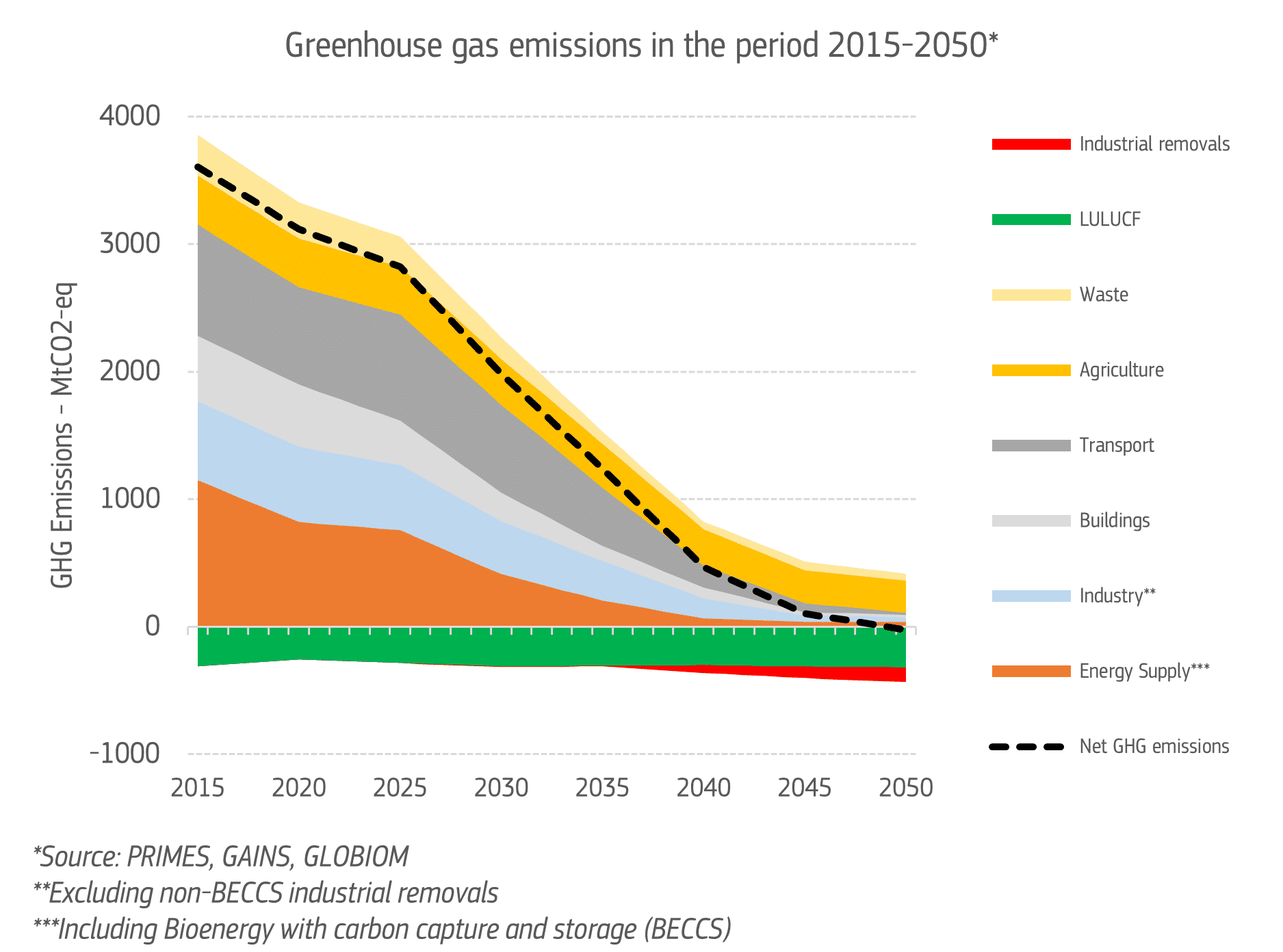

While the European Union aims to reduce the emissions of greenhouse gases, the crucial role of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) for achieving its goal of net zero emissions by 2050 remains ill-defined. The 1.5°C and 2°C scenarios of the IPCC as well as EU scenarios for net zero emissions assume some form of CDR to offset emissions of industrial processes like steel or cement production or aviation considered hard or impossible to abate. These scenarios assume that there would still be some carbon emissions but that these would be compensated by carbon sinks—either natural ones like the ocean and forests or so-called technological ones like direct air capture carbon storage. However, how these CDR technologies will work and who will finance and deploy them on which time scales is not yet settled and emerges as a hotly debated subject.

Alina Brad and Etienne Schneider—respectively senior scientist at the Department of International Politics and postdoctoral researcher at the Department for Development Studies at the University of Vienna, and both members of the Environment and Climate Research Hub (ECH)—together with Tobias Haas from the Research Institute for Sustainability at Potsdam, recently published a study in the journal Frontiers in Climate on how CDR and its deployment is being imagined by six trade associations of major economic sectors on the EU level. These associations do not challenge the EU’s overall emission reduction goal, but in most cases their visions of achieving net zero heavily rely on future CDR deployment that remains uncertain. Brad adds: “These technologies are uncertain because they partly do not yet exist at scale, their actual deployment costs are not clear, or they contain unquantified risks.”

Meanwhile, the associations ignore discussions about a deeper sustainability transformation of the economy. The researchers argue that the envisioned deployment of CDR methods should be subjected to a more substantial political discussion in order to not act as a mitigation deterrence hindering actual emission reduction efforts. Schneider adds, “The debate has to be frank about which CDR methods can be deployed sustainably at what scale, and who’s responsibility the hard-to-abate emissions exactly are.”

An Overreliance on CDR

“Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies remove atmospheric carbon to durably store it in reservoirs or in manufactured products. It can be captured from biogenic sources—like burning wood—in industrial processes or directly from the air,” Brad explains. “However, much of the imagined potential of CDR technologies relies on uncertain technological developments and massive investments for deployment.”

Techno-optimistic climate scenarios assume large-scale deployment of CDR to counter hard-to-abate emissions. In their study, the scientists focussed on the plans for CDR and residual emissions put forth by the EU-level trade associations of the cement, steel, gas, fossil fuel, chemical industry, and aviation sectors.

The researchers analysed public statements and position papers of these associations that reflect the interests they pursue in their role as industry representatives in the EU. Schneider adds, “We use the perspective of critical political economy and transformation studies to investigate how fractions of capital—i.e., companies and holders of assets invested in different economic sectors—argue for competing visions of a net zero future.”

Shifting Responsibilities

The cement industry association argues that more than half of their emissions stem from chemical processes inherent to its production and are therefore hard-to-abate. Nevertheless, the industry aims at a net zero emission target in 2050 using CDR methods. However, the plans lack concrete goals and implementation measures.

The steel industry association argues that while its production processes are energy-intensive and require fossil carbon inputs for chemical reactions, it will be able to mitigate most of its emissions by 2050. “However, to what extent this can be achieved depends on future technological innovations in steel production and CDR and sufficiently large supplies of sustainable energy and hydrogen”, Brad says, “the latter also hints at potential conflicts of allocation of sustainably produced hydrogen. Residual emissions would have to be compensated in other sectors.”

The chemical industry not only produces emissions but also needs carbon as a crucial feedstock for its production. Its trade association therefore advocates a carbon cycle economy rather than a full decarbonization which it claims would be extremely costly to reach by 2050. Residual emissions should be compensated by CDR in the chemical industry or other sectors.

The aviation sector association states that it will have to continue to rely on carbon fuels as electrification is hard to impossible. Schneider explains, “This sector aims at using hydrogen, synthetic fuels, and plant-derived agrofuels instead. The residual emissions, again, should be compensated in other sectors, also through new CDR technologies.”

The fossil fuel industry also wants to shift to hydrogen, synthetic fuels, and agrofuels for different transportation modes. However, these new fuels would still be mixed with conventional fossil fuels. Thus, CDR would be required to offset the remaining fossil emissions.

The gas industry association, in contrast to scenarios by the European Commission, assumes an increase in the use of gas with more than half of it still based on fossil natural gas. This sector also heavily relies on future CDR technologies alongside carbon capture and storage or utilization to reach net zero by 2050.

“The different industries vary in their approaches and we have not yet considered the stances of individual companies within each sector. Yet, the overall trend shows that CDR is being used as a technological panacea to align projected sector specific mitigation pathways with the climate goals of the EU while reducing the pressure to cut emissions in the near-term,” Brad summarizes. “The trade associations argue in favour of their own economic goals of securing their current capital investments and future sectoral growth and profit.”

Contradictions

“All the plans outlined by the trade associations are in line with the EU’s scenarios that do not question whether economic growth is a must,” Schneider explains. “All sectors but the steel industry have committed to net zero targets using CDR, while simultaneously often opposing concrete political measures for emission reduction in their respective sectors on the EU level.”

The net zero targets based on CDR rely on promised technological innovations that are highly uncertain, and the researchers question whether these can be scaled up in a sustainable and socially just manner to the levels envisioned by the business associations in the investigated documents. Some associations also differ in their expectations regarding the scalability of individual CDR methods, depending mostly on whether they align with or challenge current business models. All associations fail to delineate exact responsibilities and implementation pathways for CDR.

Brad adds, “The sustainable transformation of the economy that is necessary to reach the climate goals cannot purely be a win-win scenario for every industry as is often proclaimed. Some sectors need to be fundamentally changed or even dismantled.”

Brad und Schneider also work with the NGO Carbon Market Watch in order to initiate discussion on these issues related to CDR and residual emissions on the EU level. Brad was also involved in developing Austria’s carbon management strategy. She adds, “We are happy that our research also contributes to the political discourse.”

At the Environment and Climate Research Hub (ECH), Brad and Schneider network with scientists from other disciplines and use the opportunity to invite international guest researchers like Tobias Haas who collaborated with them on the recent study.

Alina Brad is a senior scientist in the field of International Politics at the Department for Political Science at the University of Vienna and member of the ECH. She is also a Coordinating Lead Author of the Second Austrian Assessment Report Climate Change. Her research interests are international climate and environmental politics, CDR technologies, decarbonization, political ecology, and socio-ecological transformation.

Etienne Schneider is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department for Development Studies at the University of Vienna and member of the ECH. His research focuses on the global political economy of decarbonization, green industrial policy and the integration of CDR into international and EU climate policies.

Further Reading:

🛈 In a Nutshell

- Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies that remove carbon from the atmosphere to durably store it in reservoirs or products are seen as crucial parts of future climate scenarios while their development and deployment at scale is highly uncertain.

- EU-level trade associations of the cement, chemical, gas, fossil fuel, and aviation sectors substantially rely on CDR methods in their net zero visions and roadmaps.

- The imagined future deployment of CDR technologies enables these associations to advance visions of reaching net zero that do not significantly challenge their business models, ignoring the need to phase-out fossil fuels and downscale certain economic activities to enable carbon-neutral futures.